Ever heard of the 1734 Murillo Velarde map and why it should be renamed?

Historian Ambeth Ocampo says it should instead be called the ‘Velarde-Bagay’ map to highlight the contribution of its Filipino engraver Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay

MANILA, Philippines – Tucked away in the basement of a castle in the English countryside once used to film the Harry Potter movies, the “Mother of all Philippine maps” resurfaced when severe flooding forced the Duke of Northumberland to sell among other heirlooms, the 1734 Murillo Velarde map.

The stroke of serendipity meant the map would finally find its way back to the Philippines after centuries. Businessman Mel Velarde – prompted by Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio – bid P12 million for the prized artifact and won during a Sotheby’s auction in 2012.

Considered the most important map of the Philippines, the 1734 Murillo Velarde map – named after its cartographer Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde – defined in vivid detail the territory of the country nearly 300 years ago. It continues to do so until today.

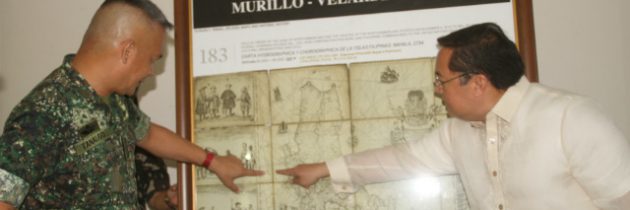

After all, a spotlight was put on the map after it played a crucial role in the Philippines’ case against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands. The map had been entered as evidence for the Philippines as it showed Panatag Shoal or Scarborough Shoal (named “Panacot” on the map) has been part of the Philippine territory as far back as nearly 3 centuries ago.

‘SCARBOROUGH IS OURS.’ The Northern Luzon Command on June 6, 2016, receives a framed replica of the 1734 Murillo Map that shows the disputed Panatag Shoal (Scarborough Shoal) as part of the Philippines.

PHOTO COURTESY OF NORTHERN LUZON COMMAND

Unlike the Philippines, China has not been able to produce a map older than this one, showing the shoal in its territory. With less than 20 copies worldwide, the Murillo Velarde map is also extremely rare and valued as the first scientific map of the Philippines. (READ: Ancient maps support PH claim over Scarborough)

But for historian Ambeth Ocampo, it’s about time the Philippines considered renaming it. Why? Because Pedro Murillo Velarde was not the only person behind the creation of the map.

What should it be called? Ocampo suggested calling the Murillo Velarde map the “Velarde-Bagay” instead.

According to Ocampo, the map is important not only for its rarity, but also because it tells us one story about who we are as Filipinos. Ocampo said while the map is largely known to have been drawn by Velarde, what’s been mostly forgotten is that it was engraved and printed by a man named Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay, who signed himself an “Indio Tagalo” on the map.

“The most important map of the 18th century is called the Murillo Velarde map, which I hope, will be renamed the Velarde-Bagay map,” Ocampo said.

“While traditionally the map should be named for the cartographer, because we’re Pinoy, we should highlight the Philippine contribution. The man may have drawn a map but without the Indio who signed, you will have no beautiful map,” he added.

For Ocampo, renaming the map to include both its creators gives credit to whom it is due.

“The map shows you not just the territory but much, much more,” he said.

Encircled in this photo is ‘Panacot’ shoal, also known as Panatag Shoal (Scarborough shoal) or Bajo de Masinloc.

SCREENSHOT FROM THE US LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

What else is in the map? Aside from laying out Philippine territory, the map also earned praise from historians, scholars, and cartographers throughout the world for depicting a capsule history of the Philippines and what life was like here in the 18th century.

Images of different types of vessels sailing in Philippine waters and the ports of Manila, Zamboanga, and Cavite, show the country’s maritime culture, which many Filipinos often forget, Ocampo said. With over 7,641 islands (according to the National Mapping Resource and Information Authority) the Philippines has one of the longest coastlines in the world.

Meanwhile, 12 vignettes that decorate the sides of the map showcase Philippine products and the daily life of Filipinos. Foreigners who were in the country at the time, such as Persians, “Cafres” (Africans), Indians, Chinese, and Japanese, among others, attest to the Philippines as a rich trading port, too.

“What’s important about the map is that in the 18th century, you’d think we’re a backwater [place but] Manila was not,” Ocampo said.

SOFIA TOMACRUZ

Source: https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/why-we-should-rename-1734-murillo-velarde-map