History

Before it was called only Andarax. It is a landscape full of trees and water due to its high rainfall. There are up to 16 different types of fountains scattered through the village.

El Zagal, last king of Almeria, spent some time here after the Capitulations of Baza, Guadix and Almeria in 1489. It was also the official residence of Boabdil after he left Granada once he had handed it over to the Catholic Monarchs. He would later leave definitively for Africa.

The first Moorish revolt in 1500 was especially dramatic for the people of Laujar as they were hiding inside the mosque and it was set on fire. Later the entire Moorish population was obliged to convert to Christianity or leave the kingdom.

In this village Fernando de Valor, Aben Humeya, was assassinated. He had been chosen as King of the Moors, in this very place, and they had rebelled in 1568. Aben Aboo also lived here, the nephew and murderer of the above-mentioned, another of the leaders of the Moorish rebellion. Two years later, the rebellion would be put down by Juan of Austria with the expulsion of the Moors from the Kingdom of Granada. This village, like many others, would be left deserted and in later years repopulation would be carried out with people from outside the Kingdom of Granada.

Nowadays Laujar is experiencing good times due to programmes to develop the Alpujarra being undertaken by different administrations. The importance of rural tourism should be mentioned; an activity that in its turn affects the agroalimentary industry and handicrafts. This all offers a promising future for this village.

Eminent citizens

Francisco Villaespesa Martin, poet.

Pedro Murillo Velarde, Jesuit historian.

Florentino Castañeda, historian.

Source: http://www.andalucia.org/en/destinations/provinces/almeria/municipalities/laujar-de-andarax/history/

Click the map to zoom in.

DATE IMPORTED:

19 June, 2015

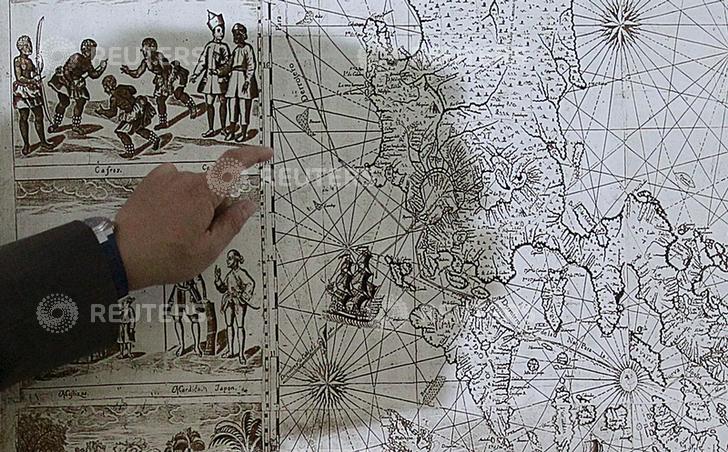

A shadow of Filipino businessman Mel Velarde is cast upon a replica of a 1734 map he bought at an auction in London, which shows the Scarborough Shoal as part of the Philippine territory under Spanish rule during a Reuters interview in Manila June 19, 2015. A nearly 300-year-old map of the Philippines showing islands in disputed waters hopes to boost the country’s claim in the South China Sea, Velarde said on Tuesday. The map, published in 1734 by Spanish priest Pedro Murillo Veralde, showed Scarborough Shoal, located around 124 nautical miles from the island of Luzon and labeled as “Panacot” in the map , as part of the Philippines territory. The original map was still in London for safekeeping, but a certified true copy was submitted to the Philippine government when it requested copies of historical maps for its UN arbitration case against China in The Hague. REUTERS/Romeo Ranoco

Source: http://pictures.reuters.com/archive/GF10000133071.html

15-Jun-2015 Intellasia | The Independent | 6:00 AM

When an ageing Victorian culvert collapsed on land owned by the Duke of Northumberland in May 2012, the effects were immediate and serious: landslips and flooding which resulted in the residents of nearby blocks of flats being evacuated and some of the properties demolished.

But nobody could have predicted that the decay of an underground drainage system in a housing estate in the west of Newcastle would result in the unearthing of a crucial piece of evidence in a bitter land dispute between the Philippines and China.

The story, involving a hard-up English aristocrat, a wealthy Filipino businessperson and a 281-year-old map, has yet to reach a conclusion but already reads like the script of a Hollywood film. Alnwick Castle, which is owned by the Duke of Northumberland and where scenes from Harry Potter were filmed, could even act as a ready-made backdrop to the drama.

After the culvert collapsed three years ago, the Duke was left facing a repair bill of up to GBP 12 million to fix the damage. To finance the project, he agreed to sell around 80 family heirlooms at an auction in Sotheby’s in London.

Lot #183 was a map drawn up in Manila in 1734 by Pedro Murillo Velarde, a Jesuit priest, which the auction house’s catalogue described as “the first scientific map of the Philippines”.

Specialists at Sotheby’s set a price of between GBP 20,000 and GBP 30,000 for the 44 by 47-inch document, but it eventually sold for GBP 170,500.

The buyer was Filipino businessperson Mel Velarde, the president of an IT firm, who lodged the winning bid over the phone from a steakhouse where he was celebrating his 78-year-old mother’s birthday. Although he was initially interested in the map because he shared a name with the cartographer, he said winning the auction became a “personal crusade” when he realised that it may prove his country’s claim to the Scarborough Shoals.

The Shoals, a group of rocks and reefs 120 miles west of the main Philippine island of Luzon, are labelled as “Panacot” on the map, which also shows them as forming part of Philippines territory. The ownership of the rocky islands has long been disputed, with both China and the Philippines laying claim.

Asked why he was so keen to secure the map, Velarde said: “In a true-to-life movie, there’s a part for everybody. There’s a bully in the neighbourhood. He already took over our land. Then, this map is owned by a Duke in a Harry Potter castle. It’s like you wanting to play your part in the movie.”

The businessperson has now given a copy of the map to the Philippine government, where it will be put to use by officials during legal debate at the UN’s Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague. A final judgement on the row is not expected until March next year.

The Philippine government are hopeful that the map may tip the balance in their favour. “China’s claim is about historical title. This old map would certainly present the side of the Philippines when it comes to any historical basis,” said Edwin Lacierda, a spokesman for the country’s president Benigno Aquino III.

The Philippines accused China of seizing the Shoal in 2012, when ships of the two nations were involved in a stand-off. When the smaller Philippine force had to withdraw, the Chinese occupied the islands.

In 2013, the Philippines requested international arbitration in the case, and last year submitted a 4,000-page dossier to support its claim of sovereignty. China has so far ignored requests to take part in the legal process.

The “Murillo Map”, as it is now known, also contains a series of 12 engravings, depicting the various different ethnic groups which lived on the islands at the time. A Filipino supreme court judge has described it as the “mother of all Philippine maps”, as it also appears to cast doubt on the so-called “nine-dash-line”, which marks out China’s claim to 90 per cent of the South China Sea.

A spokeswoman for the Duke of Northumberland told The Independent that he did not want to comment on the affair. “He’s a very private person and it all happened after the map was sold anyway,” she added.

The “Murillo Map”, as it is now known, was drawn up by the Jesuit priest and cartographer Pedro Murillo Velarde in 1734 and published in Manila. According to some historical accounts, it was removed from the Philippines in 1762 by invading British troops. The map eventually ended up in the possession of the 12th Duke of Northumberland, Ralph Percy, who sold it off alongside around 80 other heirlooms to pay for the damage caused when a Victorian culvert collapsed on his land, causing flooding and landslips. As might be expected the sizeable wall map, which measures 112cm by 120cm, it is not in the best condition. Notes accompanying the lot when it was auctioned at Sotheby’s in November 2014 warned potential buyers: “linen splitting, one panel detached, light browning”.

However, the auction house also described it as “a landmark in the depiction of the islands” and “the first scientific map of the Philippines”. Two side panels contain 12 engravings, portraying a series of native costumed figures, a map of Guam and three city and harbour maps, including Manila.

Source: http://www.rappler.com/nation/135541-murillo-map-scarborough-shoal-nolcom-afp-donation-velarde

By JC Gotinga, CNN Philippines

Updated 20:21 PM PHT Tue, June 9, 2015

An 18th century map may hold the key to solving the maritime dispute between the Philippines and China. The government is submitting a copy of it to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea this week. In this report, we find out that this map was at Hogwart’s castle for more than 200 years.

This report aired on CNN Philippines’ Network News on June 9, 2015.

Source: http://cnnphilippines.com/videos/2015/06/09/Govt-18th-century-map-to-boost-territorial-claim.html

IT WILL come as a big surprise for many that, in 1991, the 1734 Murillo Velarde map, now making front-page news, was offered with a starting bid of 10,000 German marks (P186,000) at an auction in Frankfurt!

Alerted by friends in Europe, I immediately sought out a dozen alumni willing to contribute P50,000 each to place a bid for the map. Unfortunately Mt. Pinatubo had erupted at the time and its lahar kept flooding Central Luzon. So I incurred the ire of an historian who scolded me for initiating such a project.

His tirade dwelt on the vanity of collectors and their apathy to the suffering of their fellow human beings during a national disaster.

His simplistic argument sounded like that of Judas who questioned Mary Magdalene’s “frivolous” act of pouring on Christ’s head the perfume which could have been sold and its proceeds given to the poor. The presupposition here seems that for as long as the poor and hungry are around, one should not indulge in the “guilty pleasure” of buying artworks and cultural artifacts.

But then, do human beings live by bread alone? Beyond material needs like food and housing, human beings desire meaning. Culture and art are not “luxuries” but are essential to being human, for they bestow us with meaning and a sense of self-esteem.

Culture, taken here in the broadest sense, refers to any human experience insofar as it leaves traces. It covers human works on the technical, social, economic, political, intellectual, moral and artistic levels.

These human achievements are expressed in the forms of tools, documents, monuments, actions like rituals, and works of art. To quote Hegel, these constitute “the very substance of the life of a people.” These reveal that layer of images and symbols comprising the basic ideals of a people.

It will also come as a bigger surprise that for 30 years now, a copy of the 1734 Murillo Velarde map has been in Malacañan Palace, according to a reliable source! It is strange then that no one in the national government took notice of this until Velasco Velarde’s heroic act of winning the bid and generous gesture of donating the coveted map to the National Museum.

The “truth dissemination” planned by this Ateneo alumnus could have started earlier. To quote him: “[E]very Chinese child since 1935 was taught in school that these contested islands were owned by China for centuries… We must match the indoctrination, propaganda and brainwashing of their youth with our own truth seeking and truth dissemination among our youth. A P12-million map without the accompanying follow-through programs would make that map a mere wallpaper!”

Collecting is noble

Velasco Velarde may have imparted an important lesson to collectors—that one never collects for oneself alone but for generations to come. He reminds them that artworks and cultural artifacts are not only viable as economic investments for self-gain. They are also powerful vessels for promoting esteem of one’s heritage, pride of one’s country and dedication to one’s people.

A “noble-minded” collector differs from a “hoarder,” The true collector is ever mindful that he lives in time and in the world with and for others. She is constantly aware of the intimate intertwining of the spiritual and the material—that matter is the necessary slope of the spirit. To care for the material is to assure the growth of the spiritual.

To go back to the 1734 Murillo Velarde map. It may be time to call it the Murillo Velarde-Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay-Francisco Suarez map. For not only Fr. Murillo Velarde the cartographer but also Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay the engraver-printer and Francisco Suarez the artist give us a sense of self-esteem. They deserve our gratitude.

In 1733, King Philip V of Spain ordered Governor General Fernando Valdés Tamón to prepare a map of the Philippines. Governor General Valdés immediately entrusted the task to Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde, a Jesuit professor of canon law at the Colegio de San Ignacio in Manila. According to Carlos Quirino’s book “Philippine Cartography,” Fr. Murillo Velarde was acknowledged as “the authority on maps and the best chronicles that had appeared in the archipelago.”

Considered by the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid as the “first and most important scientific map of the Philippines,” the 1734 Murillo Velarde is also a large map measuring 27 inches x 42 inches. In the first volume of his “Chronicas,” published in Manila from 1738 to 1744, the Franciscan Juan de San Antonio credited Murillo Velarde as having “placed all the towns, points, coves, ports, shoals, reefs, routes, courses, rivers, forts and distances, as was possible in so difficult a matter and within the scale. And in a description of a few lines … related the most memorable [events] therein, the most extensive possible under such a minimum of words and figures.”

Murillo Velarde’s map is regarded by former Education and Culture Minister Jaime C. Laya as “the culmination of two centuries of mapmaking” and as “the Holy Grail of Philippine cartography.” For the Jesuit historian José S. Arcilla, the map also served as a sea chart aimed at guiding ship captains to “navigate the narrow inter-island seas of the Philippines, for which waterways and harbors were clearly marked.” That is why the map includes compass roses from which radiates a network of lines on which sea pilots plotted their courses. This also explains the drawings of Moro sailboats (vintas), Chinese junks (champan), Spanish galleons and other types of sailing craft.

At the top right-hand corner of Murillo Velarde’s map, there is a magnificent cartouche with the Spanish royal coat of arms, heralded by two cherubs. Below this, two female allegories hold a curtain with the map’s title: “Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas Dedicada al Rey Nuestro Señor por el Mariscal d[el] Campo D[on]. Fernando Valdés Tamón … Hecha por el P[adre] Pedro Murillo Velarde d[e]la. Compa[ñia] de Jesus.”

On the medallion in the southwestern part of the map, there is a capsule history of the Philippines: Magellan’s arrival in Cebu, his being slain (by Lapu-Lapu) in Mactan, the founding of Manila by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi on June 24, 1571, the products cultivated, the flora and fauna, and the missionary work undertaken by the different religious orders.

Excellent painters, engravers

Having a high regard for the talent of the Indios (Filipinos) in the arts and crafts, Murillo Velarde asked the artist Francisco Suarez and the engraver-printer Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay to collaborate on 12 panels showing scenes from daily life in early 18th-century Philippines, and the local flora, fauna and landscape.

Murillo Velarde expressed his admiration in his “Geographia historica de las Islas Philipinas,” published in Madrid in 1752: “The Filipinos are extremely capable in any handicraft— there are excellent embroiderers, painters, silversmiths and engravers whose work has no equal in all the Indies, and could be considered elegant in Paris and Rome. I have seen paintings, drawings and maps from pens more beautiful, neater and handsomer than those taken from Paris.”

The 12 panels consist of four separate parts which are pasted at the sides. Each part is made of three frames (9 in wide and 7 in high). An interesting aspect to note is the cosmopolitan population of early 18th-century Philippines. Father Murillo recounts in his “Historia de la provincia de Philipinas de la compañia de Jesus” that by standing on the bridge across the Pasig River, one could see representatives of “all the nations of Europe, Asia, America and Africa passing by.”

In a first frame on the left side of the map, there are sangleyes or Chinese residents (a long-haired and bearded Christian convert, a trader with a fan, a fisherman (pescador) wearing a raincoat of palm leaves and a laborer with his carrying pole (cargador con pinga); the last three with their hair in pigtails. Below this, a frame shows a group of four half-naked kaffirs (cafres) from Africa. Three of them, with a string of small bells around their ankles, dance while a Canarin (a native of Canara, an ancient kingdom near Mangalore) and a lascar or Indian sailor look on. In a third frame, there is a family of mestizos (of mixed Spanish and Filipino blood); the man dons a hat and long cape over bloomers; the woman wears a saya (a long wide skirt) and a tambourine necklace.

In the same frame, there is a Mardican (or native of Ternate in the Moluccas) with a sword, spear and shield. After the Spanish forces withdrew from the Moluccas in 1662, the Christian Mardicans in the Moluccas migrated to a town in Cavite which they also named “Ternate.” A Japanese with a shaved head and a sword stands beside the Mardican.

Rural scene

In the first frame on the right side of the map, there is a Spanish official, dressed in the Louis XV style, a flared coat, lace cuffs and wig. He is protected from the heat of the tropical sun by his servant who holds a high parasol behind him. A negro criollo (Philippine-born Spaniard described as dark-skinned but not as dark as the Indios) is respectfully listening to the Spanish official. Behind them, two Indios indulge in the favorite local sport of cockfighting.

Farther behind them are two Aetas, with bow and arrow. In the next frame, a seated Armenian (or Persian) smokes a water pipe in front of a Mogol (with a beard and a turban) and a native of Malabar (with turban and earrings) from Goa and India’s west coast.

In a third frame, there is a street scene with a couple—a barefoot Indio, with a black cloth (lambon) on his arm, and a veiled India or native woman, with a scapular around her neck—on their way to church.

Facing them are a female vendor selling a basket of guavas held on top of her head; and two boys, one in a loincloth and holding a crab, the other naked, carrying a piece of bamboo containing either vinegar or milk. Besides the two boys, a Bisaya stands with a balarao (a regional knife). In the distance, a couple is going through the movements of the comintang, an ancient Filipino dance, to the music of a man playing a mandolin.

There is also a frame with a rural scene: a man on a ladder cutting some bamboo from a grove (with the observation that bamboo is used in building houses), a farmer riding on a carabao, a boy holding a huge bat with a head resembling that of a dog, a man being transported in a hammock and an albino monkey. In the same frame, monkeys climb a coconut tree whose sap is made into a drink (tuba). In the background, we see papaya and jackfruit (nanca) trees; also an areca nut palm tree (bonga), from which betel nut (buyo) is derived and which is chewed by the locals.

There is still another frame with a rural scene: a farmer urging his carabao to help him plow a field, another farmer with a wooden sled pulled by a carabao, a woman pounding with a pestle rice in a wooden mortar (lusong) before a nipa hut (bahay kubo). For fauna, there is a crocodile, baring its sharp teeth, a boa constrictor with its tail strangling a pig and a white crow (puting uwak) in the sky. Four frames are devoted to Intramuros, the fort of Zamboanga, the fort of Cavite and the island of Guam (Guajan).

Fr. Murillo Velarde must have been overjoyed by the naive charm of the 12 vignettes. In any case, pride is visible in the signatures of the artist and the engraver who proclaim at the bottom of the Murillo Velarde map: “Fran.[cisco] Suarez, Indio Tagalo lo hizo” (Francisco Suarez Indio Tagalo made this) and “Lo esculpió Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay, Indio Tagalo en Man.[ila] Año 1734” (Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay, Indio Tagalo, engraved this).

‘Panacot’

“Panacot” or “Scarborough Shoal” does not appear in any of the ancient Chinese maps.

The 1734, 1744 and 1760 Murillo Velarde maps clearly show Panacot, the island disputed by China, even before it became known as “Scarborough Shoal.”

In fact, as Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio wrote in his monograph “Historical Facts, Historical Lies and Historical Rights in the West Philippine Sea” and has repeatedly stressed in his lectures on the territorial dispute between the Philippines and China, Panacot has been “consistently depicted in ancient Philippine maps from 1636 to 1940.”

Only after Sept. 12, 1784, when an East India Co. tea-clipper was wrecked on one of its rocks did the shoal become “Scarborough Shoal.” For Carpio Panacot or Scarborough Shoal “does not appear in any of the ancient Chinese maps.”

Leovino Ma. Garcia is former dean of the humanities of Ateneo de Manila University. He teaches philosophy at the University of Santo Tomas Graduate School.

Source: http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/196703/mother-of-philippine-maps-settles-sea-dispute-with-china

Might this map give the Philippines the upper hand against China in the dispute over ownership of Scarborough Shoal and other islets in the West Philippine Sea?

Businessman Mel Velarde recently successfully bid for and acquired a certified true copy of what is known as the Murillo Velarde map, a cartographic sketch of the Philippine archipelago said to have been drawn by Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde and published in Manila in 1734. The World Digital Library, which carries a downloadable copy of the map, says “it is the first and most important scientific map of the Philippines.”

The site further describes the map (formally known as “Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas,” Manila 1734, or A Hydrographical and Chorographical Chart of the Philippine Islands) thus: “The map is not only of great interest from the geographic point of view, but also as an ethnographic document. It is flanked by twelve engravings, six on each side, eight of which depict different ethnic groups living in the archipelago and four of which are cartographic descriptions of particular cities or islands. According to the labels, the engravings on the left show: Sangleyes (Chinese Philippinos) or Chinese; Kaffirs (a derogatory term for non-Muslims), a Camarin (from the Manila area), and a Lascar (from the Indian subcontinent, a British Raj term); mestizos, a Mardica (of Portuguese extraction), and a Japanese; and two local maps—one of Samboagan (a city on Mindanao), and the other of the port of Cavite.”

Velarde’s copy came by way of a curious provenance: It was among the possessions of a British lord—the Duke of Northumberland, Ralph George Algernon Percy—who, needing money to help residents living in his estate whose properties were damaged by a severe flood, auctioned off some 80 items from his family collection. The prestigious auction house Sotheby’s in London held two auctions of the Duke’s heirlooms; Velarde was able to get the map at the second auction held in November 2014, for £170,500 (around P12 million).

More than curious historical value, the map may prove crucial to the case the Philippines has filed against China in the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in The Hague, which disputes China’s claim to over almost 90 percent of the South China Sea based on its so-called nine-dash line. China has said its ancient records show indisputable historical ownership of the region, an assertion that many international historians and scholars have questioned. The nine-dash-line claim was made by China only after 1947, and officially presented to the world in 2012. By then, the region had become an international flashpoint, with competing claims by countries such as Vietnam and Malaysia, and in the case of the Philippines, even actual occupation of a number of islands scattered in the area.

One tiny detail in the 18th-century Murillo Velarde map appears to debunk China’s position: It shows Scarborough Shoal, from which China drove away Philippine troops in 2012, as already part of Philippine territory at the time the map was drawn. Called “Panacot” in the map, the shoal came to be known as Panatag or Bajo de Masinloc in modern times.

In this, the map all but supports the masterly survey of 60 other ancient maps done by Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, which convincingly shows that China’s “historical ownership” of the area is a baseless claim. Even the oldest map, dating to 1136 under China’s Nan Song Dynasty, indicates that China’s southernmost territory was Hainan Island. “There is not a single Chinese map, whether made by Chinese or foreigners, showing that the Spratlys and Scarborough Shoal were ever part of Chinese territory,” according to Carpio.

Peculiarly, the Philippine government has not made fuller use of Carpio’s presentation, to bring it to a wider audience and to get more Filipinos informed about their country’s crucial claim to an integral part of its territory, now under challenge by a giant neighbor with the economic and military means to bully its weaker coclaimants despite their historically more plausible positions.

The Murillo Velarde map, which Velarde has said he will donate to the Philippine government, can jump-start this education campaign. The map, along with other pertinent evidence presented by Carpio, should make their way to textbooks and instruction manuals. More Filipinos need to be rallied to this cause.

Source: http://opinion.inquirer.net/85664/crucial-to-ph-case