The journey of the mother of all

Philippine maps back home began four

years ago

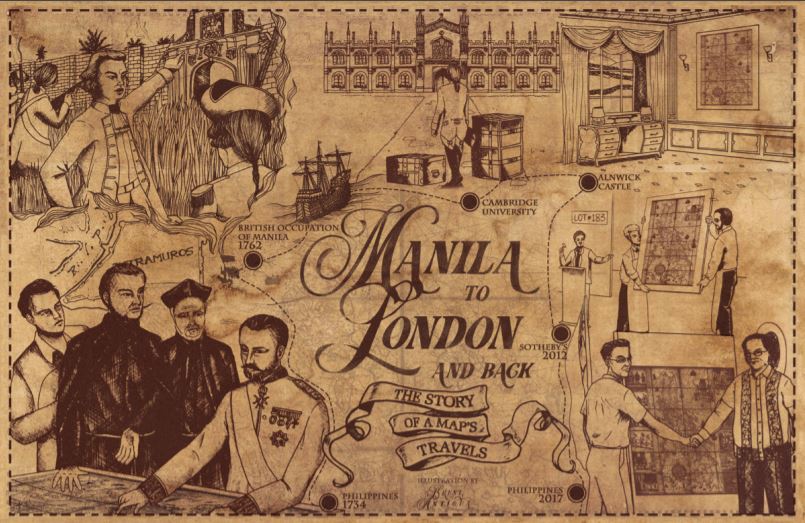

In 2014, an information technology entrepreneur was on the phone bidding in an auction in London, England, more than 10,700 km. away from Manila. Eventually, he won the bid for the 1734 Murillo Velarde map or the Carta Hydrogaphica y Chronographica de las Islas Filipinas, an heirloom of the 12th Duke of Northumberland, Ralph Percy. After winning the map at the London Sotheby’s, Velarde sent a copy to the team that would argue before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) at The Hague in the Netherlands on the Philippines’ claim on the South China Sea. The team included Supreme Court associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio The 1734 Murillo Velarde map played a crucial role in winning the Philippines’ case against China’s claim over the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea). This was on July 12, 2016. (see Map rights wrongs: the 1734 Murillo Velarde map). The Philippines now has in its public collections the country’s first and most important scientific map, thanks to the benevolence of Mel Velarde, who donated to the National Museum the map he bought at London Sotheby’s for US$273,000 (P12 million). How did the Murillo Velarde map of 1734 end up in the United Kingdom? An official map of the Spanish empire, it was commissioned by Philippine Governor General Fernando Valdes y Tamon (1729-1739) and was designed by Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde, drawn by Francisco Suarez and engraved by Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay in eight copper plates. Madee in Manila, the map shows the maritime routes from Manila to Spain and to New Spain (Mexico and other Spanish territories in the New World), an important route for the Galleon Trade. In the conflict between England and France from 1756 to 1763 (known as the Seven Years War), the Philippines found itself embroiled in the battle when Spain allied itself with France. As a territory of Spain, Manila was vital to the Spanish empire and was very much on the British’ radar. Appearing in Manila Bay and taking the Spanish forces by surprise on Sept. 23, 1762, the British fleets finally captured Manila on Oct. 6, 1762 after 12 days of fighting. In less than two days, Manila’s wall was breached, its citizens raped, tortured and killed, and its treasures looted. Among the looted artifacts was the set of eight copper plates of the 1734 Murillo Velarde map. Brigadier General William Draper, the commander of the British fleets, brought these copper plates to London and donated them to Cambridge University, his alma mater. The University then ran several new prints of the map. One of these maps was acquired by the then Duke of Northumberland who brought it home at Alnwick Castle. There, it stayed for more than 200 years. Sadly, the copper plates were later melted by the British to print their admiralty charts.

Lot #183. In May 2012, a huge portion of the properties of the present day Duke of Northumberland was damaged by a severe flood. Repairing the damage entailed millions of pounds. By 2014, the Duke announced the sale of family heirlooms to raise funds to cover the cost of repairs. Among those to be auctioned off at Sotheby’s was the 1734 Murillo Velarde map estimated between US$32,000 to US$48,000. The map, Lot #183, was put up for bid at the auction house and was eventually won by Mel Velarde at the price of US$273,000. Almost three years after the auction, the celebrated map came home on Apr. 29, 2017. It was formally turned over to the Philippine government on June 12, 2017, the country’s 119th anniversary of

Independence from Spain.

By Mariamme D. Jadloc

illustration by Brent Antigua

Source : https://upd.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/NEW-UPDATE-OCT-DEC2018.pdf

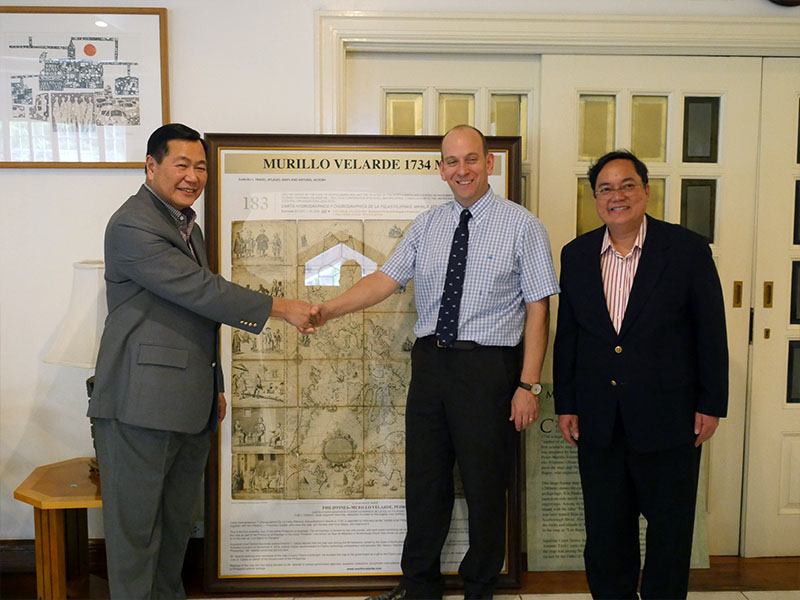

The map regarded by historians as the “mother of all Philippine maps” found its way to yet another home. On 03 October 2019, Mr. Mel V. Velarde, Filipino technology entrepreneur and educator, and Chairman and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Asian Institute of Journalism and Communication (AIJC) turned over to NAMRIA, through Administrator, Usec. Peter N. Tiangco, PhD, an official replica of the Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas Manila, 1734, otherwise known as the 1734 Murillo-Velarde Map.

MGB Director Belen gives his welcome remarks at the start of the program. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

MGB Director Belen gives his welcome remarks at the start of the program. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

Mr. Velarde talks about his gift to NAMRIA in his message. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

Mr. Velarde talks about his gift to NAMRIA in his message. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

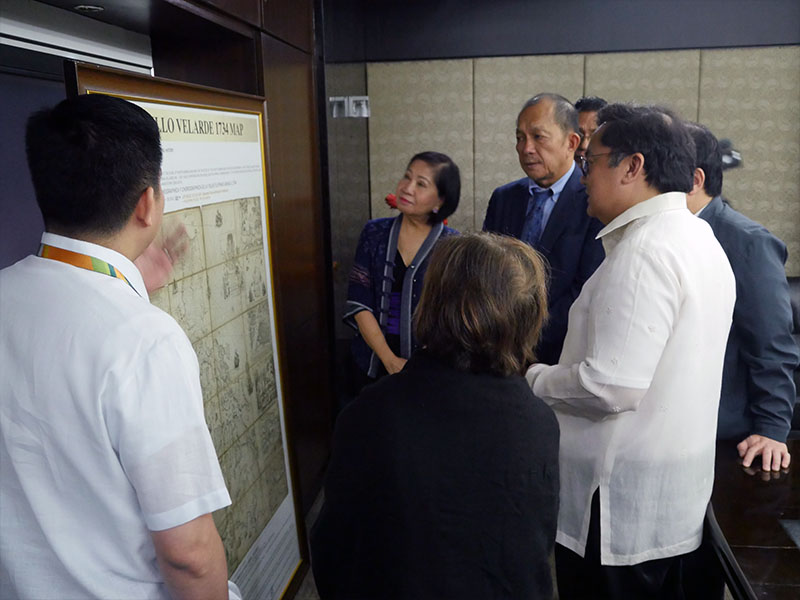

The momentous occasion was held in the NAMRIA Boardroom and was also attended by staff from AIJC, NAMRIA Deputy Administrators Jose C. Cabanayan Jr. and Efren P. Carandang, Chief of Staff Rowena E. Bongalos, Branch Directors Ruel DM. Belen of the Mapping and Geodesy Branch (MGB), Dr. Rijaldia N. Santos of the Resource Data Analysis Branch, John Santiago F. Fabic of the Geospatial Information System Management Branch, Febrina E. Damaso of the Support Services Branch, Assistant Director John M. Labindalawa of the Hydrography Branch, other NAMRIA officials and employees. The event was hosted by Engr. Charisma Victoria D. Cayapan of MGB.

The Deed of Donation is signed by Administrator Tiangco and Mr. Velarde with

The Deed of Donation is signed by Administrator Tiangco and Mr. Velarde with

officials from NAMRIA and AIJC witnessing the event. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

First made and published in Manila in 1734, the map was created by Spanish Jesuit Friar Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696-1753), together with two Filipino artisans, namely, Francisco Suarez who drew the map and Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay who engraved it upon the behest of then Governor-General Fernando Valdés Tamón, in compliance with an order from King Philip V of Spain.

The map is unveiled by Administrator Tiangco and Mr. Velarde…

The map is unveiled by Administrator Tiangco and Mr. Velarde…

…and the agreement for its donation is sealed with the customary handshake. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

…and the agreement for its donation is sealed with the customary handshake. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

Regarded as the first and most important scientific map of the Philippines by the World Digital Library, the map depicts the entire archipelago as flanked by two side panels, containing six vignettes on each side that describe various ethnic groups as well as cities and islands of the country. Also shown on the map as part of national territory are Shoal Panacot, now known as Bajo de Masinloc or Scarborough Shoal and Los Bajos de Paragua, now referred to as the Island of Spratlys.

In his message, Administrator Tiangco acknowledges the gift received by NAMRIA

In his message, Administrator Tiangco acknowledges the gift received by NAMRIA

and also its great significance. –VENER QUINTIN C. TAGUBA, JR.

Mr. Velarde gained ownership of the artifact on 04 November 2014 through an auction by Sotheby’s London in the United Kingdom. It was among the 80 heirlooms owned by the Duke of Northumberland, Ralph George Algernon Percy. Upon the recommendation of Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio, Mr. Velarde joined and eventually won the bid over the phone. The map arrived in the Philippines on 29 April 2017 and was donated by Mr. Velarde to the Philippine Government through the Office of the Solicitor General.

In his message during the turnover ceremony in NAMRIA, Mr. Velarde spoke of the map which he said was “a gift to the Filipino people” and of a public awareness campaign on it and its significance to the nation’s cultural and historical heritage. He said that the campaign involves donating official replicas of the map to different government agencies, academic institutions, and private organizations, with NAMRIA being one of the beneficiaries. In his own message, Administrator Tiangco expressed NAMRIA’s great appreciation for the gift saying “Christmas came early for NAMRIA.” Indeed, the rare map was an early Christmas present for everyone in the agency.

Monica M. Ocfemia

Source: http://www.namria.gov.ph/list.php?id=2598&alias=namria-gets-official-replica-of-1734-murillo-velarde-map&Archive=1

Historian Ambeth Ocampo says it should instead be called the ‘Velarde-Bagay’ map to highlight the contribution of its Filipino engraver Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay

MANILA, Philippines – Tucked away in the basement of a castle in the English countryside once used to film the Harry Potter movies, the “Mother of all Philippine maps” resurfaced when severe flooding forced the Duke of Northumberland to sell among other heirlooms, the 1734 Murillo Velarde map.

The stroke of serendipity meant the map would finally find its way back to the Philippines after centuries. Businessman Mel Velarde – prompted by Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio – bid P12 million for the prized artifact and won during a Sotheby’s auction in 2012.

Considered the most important map of the Philippines, the 1734 Murillo Velarde map – named after its cartographer Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde – defined in vivid detail the territory of the country nearly 300 years ago. It continues to do so until today.

After all, a spotlight was put on the map after it played a crucial role in the Philippines’ case against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands. The map had been entered as evidence for the Philippines as it showed Panatag Shoal or Scarborough Shoal (named “Panacot” on the map) has been part of the Philippine territory as far back as nearly 3 centuries ago.

‘SCARBOROUGH IS OURS.’ The Northern Luzon Command on June 6, 2016, receives a framed replica of the 1734 Murillo Map that shows the disputed Panatag Shoal (Scarborough Shoal) as part of the Philippines.

PHOTO COURTESY OF NORTHERN LUZON COMMAND

Unlike the Philippines, China has not been able to produce a map older than this one, showing the shoal in its territory. With less than 20 copies worldwide, the Murillo Velarde map is also extremely rare and valued as the first scientific map of the Philippines. (READ: Ancient maps support PH claim over Scarborough)

But for historian Ambeth Ocampo, it’s about time the Philippines considered renaming it. Why? Because Pedro Murillo Velarde was not the only person behind the creation of the map.

What should it be called? Ocampo suggested calling the Murillo Velarde map the “Velarde-Bagay” instead.

According to Ocampo, the map is important not only for its rarity, but also because it tells us one story about who we are as Filipinos. Ocampo said while the map is largely known to have been drawn by Velarde, what’s been mostly forgotten is that it was engraved and printed by a man named Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay, who signed himself an “Indio Tagalo” on the map.

“The most important map of the 18th century is called the Murillo Velarde map, which I hope, will be renamed the Velarde-Bagay map,” Ocampo said.

“While traditionally the map should be named for the cartographer, because we’re Pinoy, we should highlight the Philippine contribution. The man may have drawn a map but without the Indio who signed, you will have no beautiful map,” he added.

For Ocampo, renaming the map to include both its creators gives credit to whom it is due.

“The map shows you not just the territory but much, much more,” he said.

Encircled in this photo is ‘Panacot’ shoal, also known as Panatag Shoal (Scarborough shoal) or Bajo de Masinloc.

SCREENSHOT FROM THE US LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

What else is in the map? Aside from laying out Philippine territory, the map also earned praise from historians, scholars, and cartographers throughout the world for depicting a capsule history of the Philippines and what life was like here in the 18th century.

Images of different types of vessels sailing in Philippine waters and the ports of Manila, Zamboanga, and Cavite, show the country’s maritime culture, which many Filipinos often forget, Ocampo said. With over 7,641 islands (according to the National Mapping Resource and Information Authority) the Philippines has one of the longest coastlines in the world.

Meanwhile, 12 vignettes that decorate the sides of the map showcase Philippine products and the daily life of Filipinos. Foreigners who were in the country at the time, such as Persians, “Cafres” (Africans), Indians, Chinese, and Japanese, among others, attest to the Philippines as a rich trading port, too.

“What’s important about the map is that in the 18th century, you’d think we’re a backwater [place but] Manila was not,” Ocampo said.

SOFIA TOMACRUZ

Source: https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/why-we-should-rename-1734-murillo-velarde-map

MANILA – A copy of a rare map that helped bolster the Philippines’ case against China in a dispute over the South China Sea was sold on Saturday (Sept 14) for 40 million pesos (S$1.06 million).

The price was nearly four times what a tech executive had paid for another copy at a Sotheby’s auction in London in 2014. Mr Mel Velarde, chief executive of local telco NOW, bought his copy for 12 million pesos.

The map was expected to fetch at least 18 million pesos.

Ms Lori Juvida, a gallery owner, tendered the winning bid. She later told The Straits Times it was “for a friend”. His identity has not been disclosed but he is believed to be a Chinese Filipino.

Mr Jaime Ponce de Leon, the director of Leon Gallery, where the auction was held said: “The strength of its price is its rarity and its historical significance… As a document of history, it is very important.”

The map, first published in 1734 by the Jesuit cartographer Pedro Murillo Velarde, was among 270 maps presented to a five-man arbitration tribunal to back the Philippines’ rights to parts of the South China Sea that China was also claiming.

It drew Scarborough Shoal – referred to back then as Panacot – as part of the country’s territories. The shoal lies just 358km west of the Philippines’ main Luzon island.

The tribunal in The Hague sided with the Philippines and struck down in 2016 China’s claim to the South China Sea.

It concluded that land features, not historic rights, determine maritime claims, and ruled that the “nine-dash line” encircling two million sq km of the South China Sea on modern Chinese maps is illegal.

It upheld the Philippines’ rights to over 200 nautical miles of “exclusive economic zone”, which included Scarborough.

China, however, has ignored the ruling.

Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte raised the case with China’s leader Xi Jinping when he visited China last month. But he was told China would not change its position on the matter.

His spokesman Salvador Panelo later said the two leaders “agreed to disagree”, and that Mr Duterte would no longer bring up the ruling with Mr Xi.

The 1734 map is by itself an important historical artefact. It was engraved by printer Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay on eight copper plates. The plates were captured by Britain when it occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764, and taken to England as war booty.

The University of Cambridge used the plates to print copies of the map before the plates were “rubbed down” and re-used to make other maps.

The copy auctioned on Saturday had belonged to the Duke of Northumberland.

Fewer than a dozen copies of the map exist today. Three are with the national libraries of Spain and France, and the US Library of Congress, while another three are in private collections in the Philippines.

The map has been described as the “mother of all Philippine maps”, as it was the first to accurately represent the Philippines and define its borders. It had the names of over 900 towns, cities and villages, and showed important rivers and waterways. Later maps would use it as reference.

What also made the 1734 map unique were 12 panels on both sides, drawn by artist Francisco Suarez, that depict everyday life in the Philippines in the 1700s.

The panels portray “sangleys”- as the Chinese who settled in the Philippines were called – as well as African slaves, Armenian and Persian merchants, and a Japanese samurai.

There are also depictions of cockfighting, and men and women going to church, playing the mandolin, dancing, cutting bamboo for scaffolds, steering a carabao, and pounding rice. There are images of forts and the walled city of Old Manila.

“It was the culmination of two centuries of map-making,” wrote curator Lisa Guerrero-Nakpil.